“Even today, when I’m on the UT campus, if I turn from behind a building onto the open mall, I feel my shoulders tense involuntarily. It’s the grip of an old wariness of being exposed, of being in the line of sight from the University Tower.

On a hot afternoon in August, 1966, a student named Charles Whitman dressed up like a maintenance worker, wheeled a dolly with a footlocker packed with guns, ammunition, water and food into the Tower elevator. He rode to the top. After killing a receptionist on the top floor, he went outside onto the observation deck, braced himself against the ledge, and started shooting anyone he could line up in the scope of his deer rifle. He lined up quite a few. More than forty killed or wounded. For an hour-and-a-half, he shot at people virtually unimpeded. People were hit and crumpled to the pavement. Anyone who tried to pull the injured to safety became another target.

I was walking from law school to the main campus when people came running past me. “Somebody’s shooting!” they yelled. I had heard a string of loud reports, but didn’t think of gunfire.

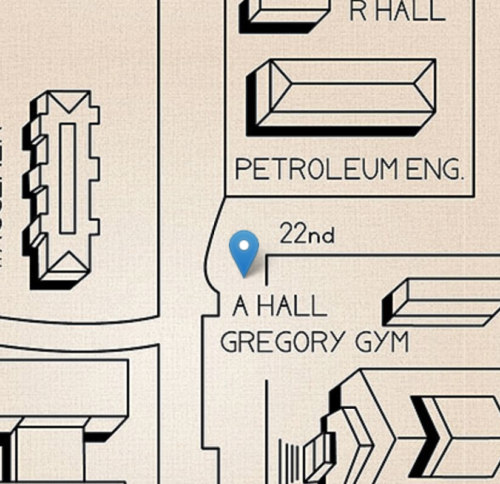

People took cover wherever they could – behind buildings, shrubs or parked cars. Some threw themselves down in the street and squirmed hard against the curb, grit grinding into their cheeks. Loud booms echoed off buildings. I crouched behind a tree near Gregory Gym and peeked at the tower. High up beneath the clock I saw puffs of dust from bullets chipping the limestone railing that shielded the sniper. After the first shock and confusion, a full-scale siege of the Tower was now underway. Later I learned that not only were the police returning fire, but college boys also had gone to their dorms to fetch the deer rifles they kept for hunting season. At the end there were dozens of policemen and students firing back at the sniper. Throughout the siege, the large clock just above the sniper continued to toll its solemn gongs every quarter-hour. Amidst the gun shots, the gongs sounded like a divine witness informing the world that notice was being taken.

Finally the firing tapered off and stopped. Word spread that it was over, that the sniper was dead. A couple of policemen with unimaginable nerve had gone up in the Tower, crept around the corners of the observation deck until they came face-to-face with the sniper, and got off the first quick shots.

During the shooting the campus seemed deserted, but now people began to appear from their hiding places behind buildings and cars and trees. People who for an hour and a half had squeezed against sun-baked curbs began to stand up. They looked dazed and wary. I went to the base of the Tower where a crowd of policemen, medical workers, news reporters and students milled about. Everyone was stunned.

A distraught woman walked up to me. She clasped her hands to her face and sobbed. “Why?” she asked. “Why did he do it?” I was in as much shock as she was, and unable to speak. I just shook my head.

Blood was smeared at various places on the sidewalks where pedestrians had been hit. The bodies of several people were wheeled past me on gurneys. They were covered with sheets, but the undraped leg of one corpse dangled from a gurney. It appeared to be the leg of a young man, dressed just as I was, in standard summertime collegiate apparel, Bermuda shorts, sports socks and loafers. The blood-streaked leg swayed back and forth as emergency workers bumped the gurney down steps to an ambulance waiting in the Inner Campus Drive. Less than two hours before, the young man was as alive and unconcerned as I had been. Meanwhile, Charles Whitman wheeled the dolly with his footlocker into the elevator, rose to the top, and went outside on the deck to start his butchery.

Whitman had begun his rampage the night before. He picked up his wife at her job, took her home, and killed her. Then he drove to his mother’s downtown apartment and killed her. He left a note saying that life wasn’t worth living and that he didn’t want his mother and wife to endure the shame he would cause them. He also requested that his brain be examined after his death.”