In the wake of the UT Tower shooting, the nation saw a change with emergency responders – including medical services. Before 1966, half of all ambulance services were run by funeral homes.

Becky Villaseñor Burrisk had an unusual childhood. She was 15 years old when Charles Whitman took to the top of the University of Texas at Austin tower and began shooting at people on the campus below. It was Aug. 1, 1966.

“I remember being in first grade and being in the morgue while dad worked,” Burrisk says.

Burrisk’s father, Charles Villaseñor, owned Mission Funeral Home in Austin. In 1966, he was in his mid-30s. On that day, Villaseñor did not just care for the dead – he also cared for the living.

Rick Narad is a professor at California State University, Chico. He says back in the 60s, operating an ambulance meant getting an injured person to the hospital – nothing more.

“Get the patient from the scene to a higher level of care and we didn’t really worry that much about any medical treatment during that time,” he says.

But in the 60s half of the ambulances in the country were actually operated by funeral homes. That’s exactly what was on Villaseñor’s mind that Monday. The family had recently gotten a two-way radio. It was on in the office.

“The call came in,” his daughter, Burrisk says. “There was a shooting down at the university at the tower.”

Her father jumped up. He grabbed one of his workers.

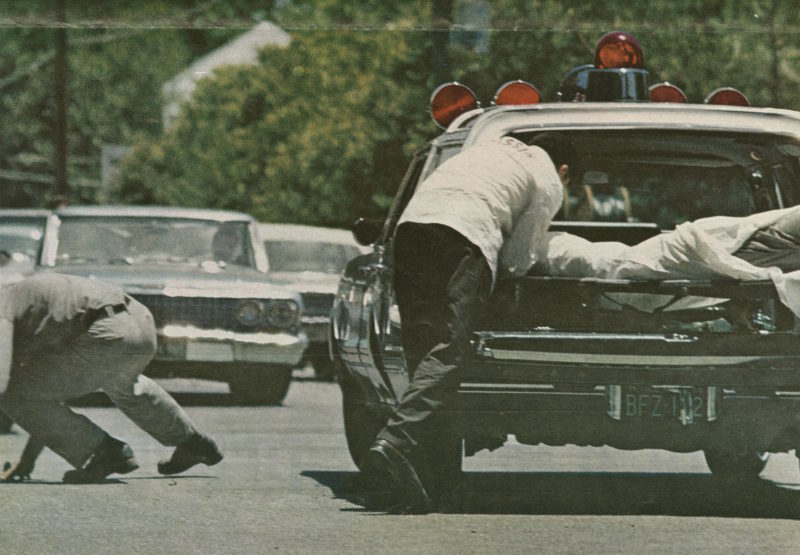

“They put on their white jackets and they were out the door,” Burrisk says.

Villaseñor was one of the first ambulance operators on scene. He and his team grabbed the wounded and took them to Brackenridge Hospital – the only trauma center in the city at the time. These funeral home workers had little medical training.

After the shooting, the National Academy of Sciences released a paper surveying emergency services across the country.

“It found that, among other things, the equipment wasn’t very good, the training was minimal, if nonexistent, and we didn’t do anything really to coordinate all the different providers,” Rick Narad says.

Government and private entities reacted – and we slowly began to see the EMS system change into what we know it as today.

Keith Noble is a commander with the Austin-Travis County EMS, which started in 1976. Paramedics now undergo nearly a year of training. They can provide medical care on the way to the hospital, and they also train alongside police officers.

“Over the last few years, we’ve been focusing on active shooter training pretty extensively with our field and command staff,” Noble says.

Noble says in these cases they’re focusing on potentially life-saving procedures like stopping bleeding and starting CPR. It’s a sophisticated model compared to 1966, when there was no protocol for a sharpshooter picking off victims – civilians, officers and funeral home directors with little direction, but lots of heart.

“There’s not a whole lot of people who have the ability to face that and to help other people through it,” Becky Burrisk says.

Burrisk says her dad never talked much about that day. But look through a 1966 cover article in Life Magazine, and you can just make him out: his back is to the photographer and he’s helping a man into the rear of his ambulance. It looks like a hearse, with emergency lights on top. On the back of his coat, you can barely make out the word: “Mission.”